I never expected inclusion in community theatre to feel like a battlefield. But here we are.

A Child Among Adults: My First Taste of Theatre

I was thirteen years old when I performed in my first professional stage production.

I was the only child in the cast. I still remember how enormous that theatre felt – the quiet hum of backstage, the older cast members laughing in the wings, the feeling of stepping into something far bigger than myself. I was a child, yes – but in that space, I wasn’t patronised or sectioned off. I was mentored. I was taught. I was invited to rise to the level of the adults around me. And I did.

That experience was formative – without it, I’m not sure I’d be in theatre at all.

Now, years later, I find myself managing a community theatre space. A vibrant one. A theatre filled with possibility, creativity, and community energy. And yet, I’ve found myself increasingly troubled by a growing pattern I’ve seen – not from audiences or artists, but from within the very structures meant to support the space.

There’s a member of our community theatre – let’s call her Anne – whose recent concerns have raised some challenging and necessary questions for me. Her strongly voiced opinions, while perhaps rooted in good intentions, have begun to carry an unsettling undercurrent – one that feels less like perspective and more like something quietly, but dangerously, prescriptive.

They resemble censorship.

I don’t believe Anne acts out of malice. But good intentions can still cause harm when they mask exclusion.

Photo by cottonbro studio on Pexels.com

On Children Performing with Adults

One of the most contentious concerns Anne raised is her belief that children (anyone under the age of 18) should not be allowed to perform in productions with adults.

Her reasoning? It’s inappropriate for children to share dressing rooms and backstage spaces with adults. That it opens the door to potential harm or “questionable” situations.

At first glance, this may seem like a reasonable safeguarding concern – and let me be clear: child protection is essential. Every theatre must have rigorous safeguarding protocols in place. No one is arguing that.

But banning children from working alongside adults is not safeguarding – it’s segregation. It is fear-based decision-making that punishes opportunity instead of managing risk responsibly.

Theatres around the world have successfully, ethically, and safely incorporated children into adult productions for decades through:

- Separate dressing rooms

- Dedicated child chaperones

- Clear backstage policies

- Vetting procedures

- Rehearsal etiquette

Children gain so much from these experiences – not just confidence, but a first-hand encounter with discipline, collaboration, professionalism, and artistic growth. This is how theatre plants seeds.

To restrict children from performing with adults is to deny them access to growth. It tells them they are not yet worthy of sharing the space. And more than that, it reflects a failure of trust in our own systems and communities.

Theatre should not be a fortress of paranoia. It should be a garden of mentorship and careful tending.

Banning children from adult casts feels like building a wall where a bridge is needed.

Photo by cottonbro studio on Pexels.com

On Queer Representation in a Children’s Pantomime

Perhaps even more concerning was Anne’s reaction to a recent pantomime staged in our theatre. In this particular show, a light-hearted, family-friendly production, the story ended with two male characters expressing romantic interest in one another.

There was no kissing, no suggestive behaviour, no innuendo. It was innocent, sweet, and delivered with humour.

Words.

That’s all.

Just words.

And maybe a cheeky wink.

Anne objected.

Anne believed the implication of a romantic connection between two male characters was inappropriate for a children’s show.

Her reasoning? It’s the parents’ responsibility to decide when and how to talk to their children about relationships, gender, and identity.

Can’t argue with that, right?

Um… actually…

Are we suggesting that theatre should not be a place for children to encounter questions, ideas, or realities outside of what their parents already endorse?

Isn’t that exactly what theatre is for?

Theatre is meant to start conversations. It always has. From the origins of Protest Theatre to Theatre of the Oppressed, from Brecht to Boal to Athol Fugard, theatre has long been a space to provoke, to engage, to inform. To hold a mirror up to society. To give voice to the under-represented. To push back against silence.

The idea that audiences – especially children – should only be shown what is already familiar, safe, or sanctioned by their parents is not only deeply limiting, but also historically dangerous. Because let’s be honest: many of the things theatre has challenged in the past – apartheid, racism, misogyny, censorship – were once upheld by families and institutions as “appropriate.”

Theatre dared to question that.

Let’s be clear – we’re not talking about anything explicit here. We’re talking about the simple suggestion that two men might fall in love, just as a prince and a princess have done in countless fairy tales. Why is that seen as dangerous, inappropriate, or “too much” for children, but the heteronormative version is standard?

I am gay and (surprise, surprise) I was once a child, too.

I watched stories that never reflected me. I internalised the absence of people like me onstage. It took years to unlearn the message that my story was not one worth telling.

What about the children in the audience who are being raised by two dads or two moms?

What about the kids who are already questioning where they fit in, and now see that once again, they’re not part of the story?

Or worse, that their story is something to be hidden or delayed?

When we say, “not at the theatre,” what we’re really saying is: not in public, not where people might see, not where it matters.

Photo by PNW Production on Pexels.com

What This Really Is: Censorship Disguised as Concern

When we say children shouldn’t perform with adults, what we’re really saying is: we can’t trust ourselves to protect them while letting them grow.

When we say queer characters shouldn’t be part of family theatre, what we’re really saying is: some families are less welcome here than others.

When we mask our discomfort as “values”, we’re not building safe spaces – we’re building walls.

As someone who believes deeply in what theatre can do – how it can transform, educate, include, and heal – I find these ideas profoundly dangerous. They chip away at the very purpose of theatre: to reflect life, to invite questions, to hold a mirror up to society. Even pantomime – yes, even silly, pun-filled, jukebox pantos – have the power to show us who we are.

Why I’m Speaking Up – And Asking You To Join Me

Because silence is complicity.

Because I’ve seen what theatre can do for a young person, and I won’t be part of denying that to others.

Because I know what it’s like to grow up queer, to search for yourself in stories and stages – and come up empty.

Because our theatre is a community space, and a community is made of many voices, many identities, and many experiences.

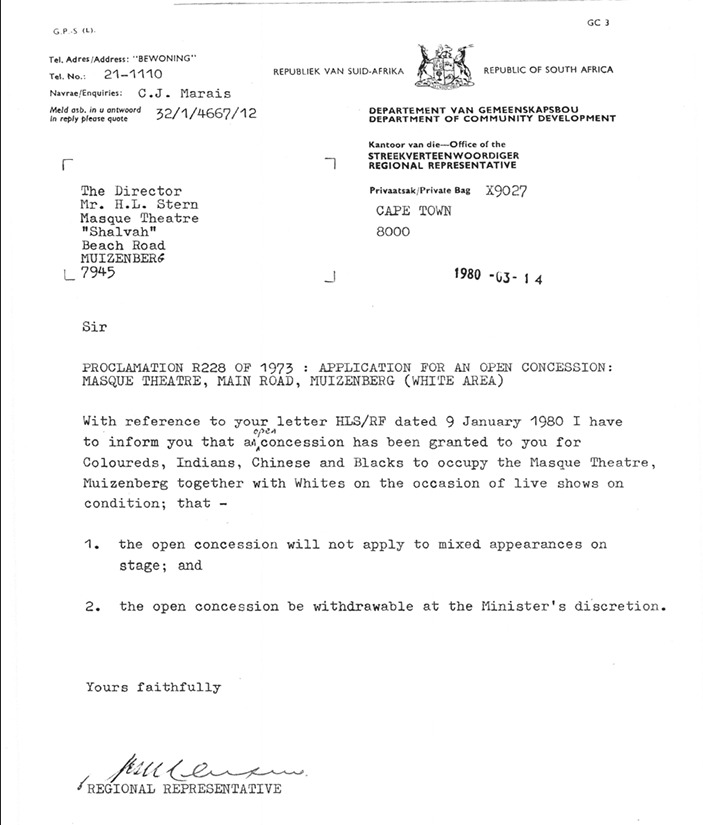

It wasn’t too long ago in South Africa that we had laws – actual apartheid laws – that determined who could share the stage, who could sit in the audience, and who was allowed to speak, sing, dance, or tell their story on stage.

Theatre was segregated by race. Audiences were segregated. Stories were censored.

We’ve spent decades trying to climb out of that history – and we must be careful not to slide back down a new slope, disguised in different language.

Exclusion is exclusion – whether it’s about age, identity, or discomfort with difference.

We’ve learned the hard way, in this country, that the moment we start deciding who shouldn’t be allowed to share the stage, we’re in dangerous territory.

Theatre belongs to everyone.

And when someone – anyone – tries to gatekeep who gets to be seen, who gets to speak, and who gets to belong… I will not stay quiet.

I’m Asking Fellow Theatre-Makers, Audiences, Storytellers: What Do You Think?

I don’t claim to have all the answers. I know this is a complex space, especially when it comes to safeguarding, representation, and community dynamics. But I also believe that when we stop asking questions, when we stop being willing to sit in discomfort, we lose what theatre is really for.

So, I’m asking:

- What does inclusion look like in your theatre?

- Where do you draw the line between protection and censorship?

- How do we tell stories that reflect all of our audiences, without erasing the ones that make us uncomfortable?

- What role should theatre play in shaping the values we pass on to the next generation?

Whether you’re a parent, a performer, a director, a board member, or someone who simply loves a good show – I’d really like to hear from you.

This isn’t just about policy. It’s about culture. About the stories we tell. About the spaces we choose to create.

That’s what’s at stake. That’s why we tell stories. That’s why this matters. Because when theatre starts taping over eyes and mouths – even gently, even politely, even with the best intentions – we’ve lost the plot.

“Theatre is a form of knowledge; it should and can also be a means of transforming society.”

— Augusto Boal

Let’s talk. Let’s listen. Let’s act. Let’s build something better – together.

Share your thoughts in the comments, or write to me. I’m listening.

Leave a comment